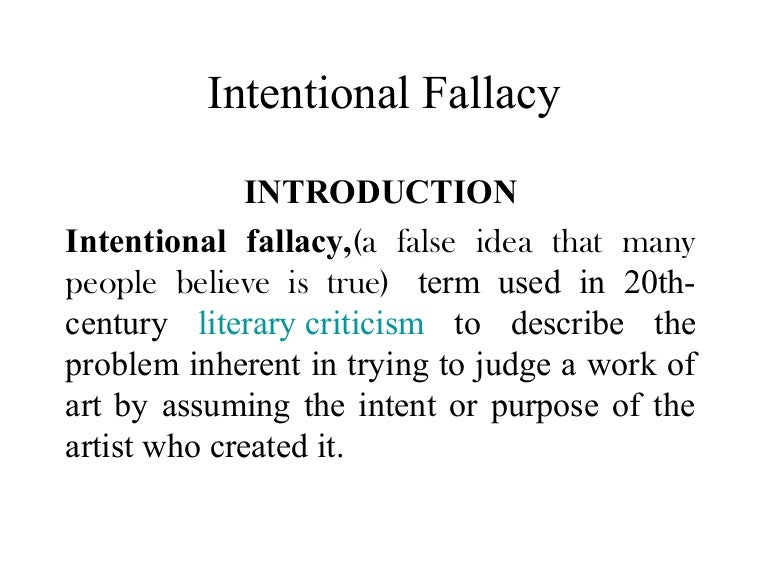

It is impossible, then, for a poem to be pure emotion (38), which means that a poems meaning is not equivalent to its effects, especially its emotional impact, on the reader (Leitch et al. It refers to the error of placing too much emphasis on the effect that a poem has on its audience when analyzing it. Wimsatt and Beardsley consider this strategy a fallacy partly because it is impossible to determine the intention of the author indeed, authors themselves are often unable to determine the intention of a poem and partly because a poem, as an act that takes place between a poet and an audience, has an existence outside of both and thus its meaning can not be evaluated simply based on the intentions of or the effect on either the writer or the audience (see the section of this article entitled The Affective Fallacy for a discussion of the latter 5).įor Wimsatt and Beardsley, intentional criticism becomes subjective criticism, and so ceases to be criticism at all.įor them, critical inquiries are resolved through evidence in and of the text not by consulting the oracle (18). The only reservation the theorist need have about such critical impressionism or expressionism, says Wimsatt, is that, after all, it does not carry on very far in our cogitation about the nature and value of literatureit is not a very mature form of cognitive discourse ( Hateful Contraries xvi).Įach of these texts codifies a crucial tenet of New Critical formalist orthodoxy, making them both very important to twentieth-century criticism (Leitch et al.

He allows, for example, for what he calls the literary sense of meaning, saying that no two different words or different phrases ever mean fully the same (Verbal Icon xii). It first appeared in Essays in Criticism at Oxford some years ago 1954, and was in part, I believe, an answer to an essay written many years ago, about twenty at least, by a friend of mine, Monroe Beardsley, and myself, called The Intentional Fallacy. Your question, I think, was prompted by that very fine essay of Father Ongs, The Jinnee in the Well-Wrought Urn, which you read in his book The Barbarian Within 1962: 15-25. Eliot and the writers of the Chicago School, to formulate his theories, often by highlighting key ideas in those authors works in order to refute them. Wimsatt also drew on the work of both ancient critics, such as Longinus and Aristotle, and some of his own contemporaries, such as T. He was a member of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Wimsatt was considered crucial to New Criticism (particularly New Formalist Criticism 1372). His major works include The Verbal Icon: Studies in the Meaning of Poetry (1954) Hateful Contraries (1965) and Literary Criticism: A Short History (1957, with Cleanth Brooks ).

He wrote many works of literary theory and criticism such as The Prose Style of Samuel Johnson (1941) and Philosophic Words: A Study of Style and Meaning in the Rambler and Dictionary of Samuel Johnson (1948 Leitch et al.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)